A Queen Unleashed

Consolidating Power for A Child King

Dr Lucy Dean

Centre for History,

University of the Highlands and Islands.

The murder of James I in February 1437 sent shock waves around Scotland. Unpopular though he might have become to many, he was also at the peak of power. He built a palace of monumental stature and a religious foundation to be his mausoleum, curtailed the power of some of his major enemies, and produced a male heir and six daughters, the eldest of whom had recently been married to the heir to the throne of France. The treacherous killing of James I posed an immediate threat to his young heir, aged only six at the time of his father’s demise, the position of his mother and the stability of the realm more broadly. As discussed in King-Slayer Seized, The First Traitors Executed at Edinburgh and The Queen’s Revenge, retribution was swift and the queen was at the heart of this action.

James I had to be buried with honour, and his son had to be crowned

It was vital that Joan Beaufort and James I’s counsellors consolidated power for the young James II in visual and tangible ways: James I had to be buried with honour and his son had to be crowned. This blog explores how these the rituals of royal death and succession were undertaken in the aftermath of James’ murder and why they were so important.

The king’s wounded body was displayed in public as proof of death

Much of the ritual action following James I’s murder appears to have been directed predominantly by the widowed queen, even though her role is often underestimated. Joan’s first act was a conscious political move. The king’s wounded body was displayed in public as proof of death. Displaying a body in death as part of the public mourning ritual was not unusual in the medieval period; however, displaying it ‘wounds and all’ was less common, especially for a king. This act was a bold and open accusation against the perpetrators and, most potently, it also appears to have been an attempt to have James I recognised as a martyr.

It was fortuitous for Joan that the visiting papal legate, Bishop Urbino, was present in Perth at this time. An account from the contemporary Book of Pluscarden records his reaction on seeing the wounded body:

[The bishop of Urbino] uttered a great cry with tearful sighs and kissed his piteous wounds, and said before all bystanders that he would stake his soul on his having died in a state of grace, like a martyr…

Joan’s actions in displaying James’ body illustrate an effort to engage wider European interest in the memory of her husband

Popular devotional cults connected to secular martyrs were uncommon in Scotland, but they were prominent elsewhere including England. As such, Joan’s actions in displaying James’ body illustrate an effort to engage wider European interest in the memory of her husband. Such speed and precision of ritual action assisted the queen in securing power for and over her infant son, even if only for a short time.

The display of the wounded body served a certain purpose, but it was not a dignified way to transport a king to his burial site. Thus, the procession from the Blackfriars to the Charterhouse would have included an enclosed and covered coffin, illustrated in Bower’s fifteenth-century chronicle, or an effigy representing the king as used in the funeral of Henry V, an event that James and Joan had attended in 1422. Chroniclers have much to say about the murder of James I but they offer little on the funeral arrangements.

The crusade-like journey of James I’s heart is interestingly reminiscent of the more well-known crusade journey of Robert Bruce’s heart

It is known that James’ heart was removed as the Exchequer Rolls record two payments in 1444–5 to a knight of Saint John of Jerusalem returning from Rhodes bearing the heart of King James I. Removing the heart and burying it at a separate site to the body, in order to maximise prayers for the dead, had been common in elite mortuary practice in the centuries prior to James’ death, but separate heart burials were far less fashionable by the fifteenth century. The crusade-like journey of James I’s heart is interestingly reminiscent of the more well-known crusade journey of Robert Bruce’s heart (c. 1329-1330). As well as making a link to one of Scotland’s most famous hero warriors, the journey of James’ heart to Rhodes, on the pilgrim route to Jerusalem, would have enhanced Joan’s efforts to have James recognised as a saint. Whilst the return of the heart was about six or seven years later, the heart must have been removed shortly after James’ death. The remarkable journey of James’ heart remains rather elusive as there are no descriptive records detailing the journey, but it was clearly part of the queen’s larger programme of memorialising her husband in the wake of his murder.

Joan Beaufort (Wikipedia)

The burial of the king was important, but the queen’s position was reliant on her personal control of the young king who had already been removed to the safety of Edinburgh Castle. As such, the funeral was likely a relatively swift affair, unlike the elaborate event James I would likely have planned, so that the queen could quickly reunite with her young son and arrange his coronation. As explained in Making Scottish Kings at Scone, the traditional site for Scottish coronations to this point had been Scone. The king’s murder at nearby Perth made this option less palatable and Edinburgh became the focus of attention for the subsequent ceremonial transition of power, with the young James II’s coronation taking place in the abbey of Holyrood.

The Chapel Royal at Holyrood Abbey in the reign of James VII of Scotland (r. 1685-1688)

D.S. Williams, History of the Abbey and Palace of Holyrood (Edinburgh, 1852)

Unlike Scone, where the king was enthroned outside, on the Moot Hill, the coronation ceremony at Holyrood largely appears to have occurred within the abbey – see: Making Scottish Kings at Scone (and, coming soon, Making Scottish Kings: 1437 and Beyond). Before and after this ritual, the young king, James II, was paraded between Edinburgh Castle and Holyrood in a public coronation procession, perhaps mirroring the celebratory return of his father and Joan in 1424, with crowds clapping welcome for the new king on 25 March 1437.

Robert Stewart and John Chambers were fastened to large crosses mounted on a cart with blood running from open wounds

Just weeks, or even days, before James II’s coronation, however, the streets of Edinburgh had hosted a very different type of ritual: the violent torture and execution of two of the first of the conspirators involved in the murder of James I. The English contemporary, John Shirley, recorded that after public torture and confession, the near naked Robert Stewart and John Chambers were fastened to large crosses mounted on a cart with blood running from open wounds and processed around the streets of the capital. Moreover, in the days following the coronation the execution of the earl of Atholl, which ended with an iron crown fitted onto his decapitated head, also took place in Edinburgh. In placing this juxtaposition of the punishment of the accused murderers and the celebration for the new king’s accession in the same ritual space, Joan was projecting a very clear message to the crowds that witnessed this scheme of events, brutally emphasising James II’s right to succeed his murdered father. The crimes of these men had made James II into a king before his time and any hope of a peaceful ceremonial transition from an elaborate funeral at Perth followed by a coronation at Scone had been violently overturned. However, these crimes did not go unchallenged as death and succession were intimately interconnected in Edinburgh’s streets.

Joan was projecting a very clear message, brutally emphasising James II’s right to succeed his murdered father

The queen’s influence rapidly waned after 1437. Nonetheless, Joan Beaufort was undoubtedly prominent in organising the dramatic transition of power following the murder of her husband. Whether she can be described as a queen ‘unleashed’ following the murder of her husband is something for you to decide!

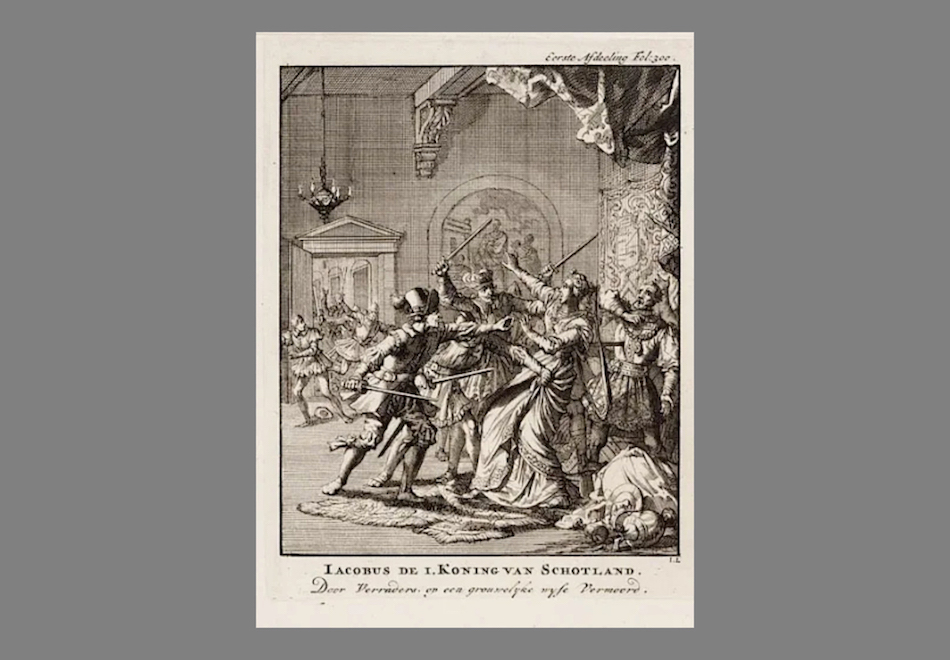

Featured Image: 17th- century depiction of James I’s assassination – Wikipedia (Public Domain)