Kate Barlass – Catherine Douglas

History, Myth and Modern Folk Tale

Part 1

Historical Sources and the Legacy of one Dodgy Dundonian

Professor Richard Oram

Romance, myth and history have been closely interwoven in the many re-tellings of the life and reign of King James I that began almost immediately after his brutal slaying in Perth. James I, both as a ruler and as a man, had a character suited to multiple interpretations. He was a poet, lover, lawmaker, bringer of justice and peace, pious, innovatory, violent, vindictive and predatory. Colour and glamour surrounded him as much as blood and violence. During his lifetime, however, he clearly attracted sharply contrasting opinions and, amongst the ruling elite at least, he was a divisive figure who drew both unswerving devotion and unwavering enmity. The personal animosity of Robert Graham towards James climaxed in the King’s violent slaughter, but it was the loyalty and devotion of James’s followers that ensured the failure of the wider plot involving the Atholl Stewarts. Indeed, the themes of loyalty and faithful service that are so interwoven into the story utterly submerged the counter-narrative of rightful resistance in the face of tyranny and oppression. Unsurprisingly, it was the high drama and heroism of James’s closest familiars amidst the violence of that February night and not the deep, treacherous involvement of several Perth families in the conspiracy and regicide that became embedded in the popular consciousness.

Amongst the most widespread of the stories that have grown up around the murder of the King is the tale of Kate Barlass

Amongst the most widespread of the stories that have grown up around the murder of the King is the tale of Kate Barlass, otherwise known as Catherine Douglas. She has inspired songs, poetry and paintings, mostly produced in the nineteenth and earlier twentieth centuries, some early feminist discussion, website entries and an entry in The Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women and has enjoyed a resurgence in popularity in the last decade, with new songs and artistic portrayals. Yet, for all of that she remains an elusive figure and, as I will explore below in this first part of an exploration of the development of the Catherine Douglas legend, she appears to be the result of an early sixteenth-century historian’s error. To add to the problem, the shared name Catherine has led to some more recent confusion with the wholly fictional character of Catherine Glover, the heroine of Sir Walter Scott’s historical fiction, The Fair Maid of Perth. The two Catherines and the stories of which they are part are inextricably bound up with the historical events that led to the death of David, duke of Rothesay, the elder brother of James I, in the case of Catherine Glover, and the assassination of James himself in Perth in February 1437 in that of Catherine Douglas. This shared link with the two sons of King Robert III, however, is not the only thing that perhaps they hold in common; both might be equally fictional.

Catherine Douglas trying to bar the door. Gordon Browne (1858-1932)

(from a history of the Scottish People published 1893)

If we peel away the onion-like layers of later elaboration that surround her, we find that the core elements of the story of Catharine Douglas have far deeper historical roots than the early nineteenth-century origins of Scott’s wholly invented Fair Maid of Perth. Even in its basics, as presented in sixteenth-century accounts, the Douglas story is a stirring tale and, in the detail of the events at Blackfriars on the night of 20/21 February that it contains, carries strong currents of plausibility.

She thrust her arm through the brackets for the missing bar to hold the door shut

Stripped of obvious late varnishings, what we are presented with is an individual named Catharine Douglas who as a lady-in-waiting to Queen Joan. It was this young woman who, when the assassins are heard approaching the royal apartments at Perth, was instructed by the Queen to bar the door against them. Finding that the drawbar had been removed and the staples for the bolts deliberately broken, she thrust her arm through the brackets for the missing bar to hold the door shut. Although the strong men outside soon broke her arm and forced Catherine aside, she had gained James sufficient time to escape into the latrine pit beneath the floorboards. Injured, she played no further part in events but went on to recover. Later versions of the story add that it was through this act of using her arm as a drawbar that she gained the nickname ‘Bar-lass’ for her heroism in using her body to keep the King’s assassins at bay. This evolution of the Barlass tradition is explored in Part 2 of this blog.

A fayre lady was soore hurte and cruelly wounded in the backe

Several of the story’s basic facts can be corroborated by details in contemporary accounts, but chiefly from the English narrative offered by the Englishman, John Shirley, who seems to have received his information directly from a Latin account that had been composed by someone with first-hand information from a member of Queen Joan’s household. First, it was well known to contemporaries that the means of securing the outer door to Queen Joan’s rooms had been removed and the door-locks broken; this had been the main act committed by Earl Walter’s grandson, Robert Stewart. Second, it was also known that the queen with her ladies-in-waiting and other gentlewomen present in her chamber had run to the door ‘to kepe the saide doore as welle as thei myght’ and managed to impede the attackers’ entry. Third, when Sir Robert Graham and his companions finally broke in, in their mad in-rush ‘a fayre lady was soore hurte and cruelly wounded in the backe’. Finally, when James thought the would-be assassins had left, as the Queen’s ladies were helping him out of the latrine pit, one of his helpers tumbled into the confined space with him. So, we have a throng of ladies with Queen Joan, all of them together seeking to hold shut the door, one being injured in the back when the men pushed in, and one – whose name is reported by Shirley as Elizabeth Douglas – finally falling into the latrine pit while trying to pull the king out. So, no individual act of heroism, just a group effort to keep shut the door, and no broken arms but rather a wound inflicted by a bladed weapon in one (un-named) lady’s back.

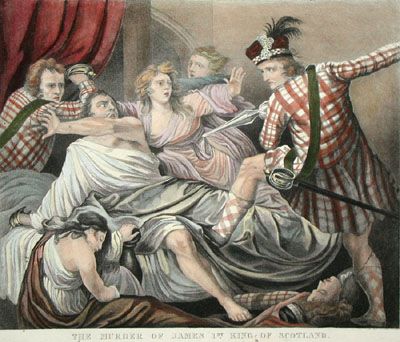

Murder of James I (19th century artists impression)

This basic narrative is where the story stuck until 1527, some ninety years after James’s assassination, when the Dundonian scholar and senior academic at the new University of Aberdeen, Hector Boece, published his Scotorum Historiae. As a Dundonian myself, five centuries on it is still an embarrassment that Boece’s Latin chronicle, translated into Scots by John Bellenden in 1531, is so notoriously riddled with error, fantasy and invention. Many deeply rooted but utterly unfounded popular traditions about Scotland’s medieval past first appear in Boece’s text and gained their currency from the fact from the 1530s down to the late eighteenth century it was the main source of information on the kingdom’s history widely available to scholars.

It is Boece who first named the Queen’s lady-in-waiting as Catherine Douglas and introduced the idea of her arm being broken whilst trying to hold shut the door.

Its span covered the era from Scotland’s semi-mythical origins as a kingdom down to the death of James I and the level of corroborable detail within it increases in its later parts. Nevertheless, even in what was to Boece the recent past there are serious errors of chronology, misnaming of individuals and misidentification of relationships, roles and titles. One of those errors is critical for the later development of the Kate Barlass story; it is Boece who first named the Queen’s lady-in-waiting as Catherine Douglas and introduced the idea of her arm being broken whilst trying to hold shut the door. He added further detail that loaned an air of greater substance to the narrative, principally that Catherine went on to marry Alexander Lovel, the laird of Ballumbie, an estate some 6km north-east of Dundee. This proximity to Boece’s hometown has been argued to lend weight to the account; as a local boy, Boece would supposedly have been aware of the traditions concerning the ancestry of prominent families in the surrounding district. Aware he might well have been, but accurate in his transmission of detail he most certainly was not.

A depiction of female courage: ‘Kate Barlass’ in a children’s history book from 1906

Can we link the wife of a fifteenth-century Angus laird to the inner circle of attendants around Joan Beaufort? Records of the Lovels of Ballumbie are fragmentary but their later fourteenth- to early seventeenth-century lineage can be recovered from a number of scattered sources. No pairing of an Alexander Lovel with a Catherine Douglas can be found among them. Alexander does occur once as a forename in the Ballumbie line, being the name of the head of the Lovel family in the last quarter of the fifteenth century, when Boece was a boy in Dundee. This Alexander, however, lived into the early 1500s and was at least a generation too young to have been of marriageable age in the late 1430s. The correct generation for the events of 1437 was represented by Alexander’s father, Richard Lovel of Ballumbie, whom we know to have been politically active between the 1420s and 1460s. A link between this man and a woman bearing the same name as John Shirley’s lady-in-waiting who was involved in the attempt to aid the King’s escape in 1437 occurs in a royal confirmation dated 29 October 1463. That document recites two earlier charters, one by the late Alexander Lindsay (d.1438), 2nd earl of Crawford, and the second by his son the 3rd Earl, both granted in favour of Richard Lovel. The first of these, dated at Dundee on 28 August 1438, concerned Earl Alexander’s re-grant to Richard and his wife jointly of the lands of Murroes in the Earl’s barony of Inverarity in Angus, which Richard had resigned to him to allow its re-settlement on himself and his wife. The lady in question was named as Elizabeth Douglas, described further as the niece (neptis) of Earl Alexander. So, rather than Alexander Lovel and Catherine Douglas, we have the marriage of Richard Lovel with Elizabeth Douglas. What cannot be proven beyond doubt is that this lady was the same woman as was named by Shirley as one of Queen Joan’s ladies.

Her possible injuries perhaps stemmed from her rather undignified tumble into the latrine pit beside the King

While it cannot be established as concrete, the circumstantial evidence is strong that Richard Lovel’s wife was a former member of the Queen’s circle of personal attendants. This Elizabeth Douglas of the 1438 charter was a woman of very distinguished descent. Her father was Sir William Douglas of Lochleven, head of a senior cadet branch of the important Douglas of Dalkeith line, and a close supporter of King James in the 1430s. Indeed, King James trusted him sufficiently to place his nephew, Archibald, 5th earl of Douglas, in Sir William’s custody at Lochleven Castle in 1431 during a period of tension between the King and his nephew. Her mother was Marjorie Lindsay, daughter of David Lindsay, 1st earl of Crawford, and Elizabeth Stewart, daughter of King Robert II. Her own name honoured that royal descent, which distinguished her as a cousin of the King. Indeed, the naming pattern of the women throughout this lineage celebrates their high birth and traces that back to Robert II’s mother, Marjorie Bruce, daughter of King Robert I. So, although there is no hard evidence to support the suggestion, this distinction and royal kinship makes it highly possible that this Elizabeth Douglas was indeed the lady-in-waiting named in John Shirley’s account of the assassination. If that is the case, then her possible injuries perhaps stemmed from her rather undignified tumble into the latrine pit beside the King rather than being the result of using her arm as a replacement drawbar.

Catherine was bot young, and her bonis not solide

Boece, then, was clearly aware of traditions surrounding a Douglas lady who married into the family of Lovel of Ballumbie and her role in the events of 20/21 February 1437. Equally clearly, however, he was unaware of hard factual details. What he presented was both seriously garbled and, probably, substantially embellished to add colour to the account. It is only from the 1527 publication of his account, for example, that the motif of the Queen’s attendant thrusting her arm into the drawbar staples gained currency. It was probably John Bellenden’s 1531 Scots translation of Scotorum Historiae that did most to broadcast the tradition amongst a readership wider than Boece’s Latin-reading university graduates. It was not quite a literal translation but expanded upon Boece’s text in a number of points and added several more errors in the detail of events. According to Bellenden, it was because ‘Catherine was bot young, and her bonis not solide’ (Catherine was only young and her bones not solid) that her arm, which she had ‘schot […] into the place quhare the bar suld have passit’ (pushed into the place where the bar should have passed), was so easily broken. The key elements of the developed legend were all in place. What was missing, however, was any mention of the ‘Barlass’ nickname.

Catherine then slammed it shut once more and put her arm where the bar had been

After Boece/Bellenden, the story began to be repeated and, in each repetition, gained added layers of detail. George Buchanan’s Rerum Scoticarum Historia, first published in 1582, added little to the storyline, which was essentially an almost verbatim repetition of Boece. John Leslie, bishop of Ross’s Latin history, first published in 1578, however, contained a level of detail present in no earlier account, all of which owed more to his imagination than to factual evidence. Leslie created a still further elaborated and extended description of the unfolding scenes within the royal apartments, which had ‘Catherine’ witness the death outside the door of the king’s page, Walter Straiton, and, quickly recognising the intentions of the attackers, slam the chamber door and shoot across the drawbar – which was still in place rather than having been removed by Robert Stewart – to bar their entry. This prevented the would-be assassins from entering the room but a traitor amongst those inside – whom Leslie names only as ‘John’ – threw the bar aside and let the door burst open. ‘Catherine’ then slammed it shut once more and put her arm where the bar had been, managing to hold the door closed for a brief but vitally important momentary respite before the bone was broken and she was thrust aside.

Like Boece fifty years before, Leslie’s narrative was translated into Scots, this time by the exiled Scottish monk James Dalrymple, whose 1596 translation circulated widely in the British Isles and on the continent. This Leslie/Dalrymple version of events was the most elaborate yet, adding in further detail that creates a colourful and richly textured tale of feminine heroism and unquestioning loyalty. The fact that the whole thrust of Leslie’s history was towards the rights of the Stewart monarchy in Scotland and the loyalty due to them by their subjects gave this particular display of devotion to the kingdom’s ancient rulers especial importance and, in the author’s eyes at least, justified its embroidery. Throughout all of these later sixteenth-century works, however, despite the deepening layers of detail, the lady in question remained ‘Catherine Douglas’ or, simply, a young woman of the ‘race of Douglas’. There was still no hint of the ‘Barlass’ naming legend.

Kate Barlass (Golden book of famous women 1919)

by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale

Despite the prominence given to the heroic ‘Catherine Douglas’ in every account from Boece onwards, the circulation of the tale was still limited to a narrow circle of the university-educated and book-buying members of Scotland’s population. Wider currency for the story came only in 1827, three hundred years after Boece’s account was first published, when Queen Joan’s lady-in-waiting and her arm formed part of the narrative of events presented by Sir Walter Scott in the first volume of Tales of a Grandfather, the accessible history of Scotland that the prolific novelist and antiquarian had been commissioned to write. Scott, however, drawing on both Boece and the Shirley account of the assassination, reconciled the different names and sequence of events in their narratives by having two separate Douglas women present, Catherine, whose arm was broken, and Elizabeth, who fell into the privy pit. The inclusion of the same version of events in the 1829 History of Scotland of Patrick Fraser Tytler ensured that the two Douglas ladies became fixed elements in the expanding literary canon. The popularity of Scott and Tytler made certain that the romantic description of the devoted maiden risking injury or disfigurement to save her king became familiar to readers throughout Britain and internationally.

Only one authority makes any mention of the Kate Barlass tradition

All subsequent mainstream Scottish histories into the later nineteenth century – and indeed throughout the twentieth – maintain the essentials of the Catherine Douglas narrative, several with the same dual Catherine/Elizabeth Douglas storyline. Only one authority makes any mention of the Kate Barlass tradition, the Dundee minister, poet and literary scholar, the Rev George Gilfillan in his 1860 study Specimens with Memoirs of the Less-known British Poets. One chapter in this volume examined the reputation of James I as the poet king but provided a summary account of his reign and death as a preface to an exploration of The Kingis Quair, James’s one certain composition. For the most part, Gilfillan follows the by-then standard account, adding only that Catherine’s arm was ‘broken in a moment, and she sinks back, to bear, with her descendants – a family well known in Scotland – the name of Barlass ever since’. This addition seems, at first glance, to be an entirely inexplicable intrusion of ahistorical opinion by the otherwise meticulous Gilfillan, but the answer to it lies in his family background. Gilfillan was born in Comrie in Perthshire, some 40kms west of Perth, the son of a Secession minister the Rev Samuel Gilfillan. His mother was Rachel Barlas, daughter of the Rev James Barlas, the Secession minister in Crieff, 8km closer to Perth. It seems that George Gilfillan could not miss the opportunity to advance a tradition that may have been circulating in his mother’s south-east Perthshire family, but which seems to have had no wider currency. Well-known the Barlases may have been to Gilfillan, yet to the 1862 author of The Origin and Signification of Scottish Surnames, Clifford Sims, Barlas(s) was unknown as a Scottish family name. Even the normally indefatigable George Black, whose 1946 Surnames of Scotland is still the principal source used by Scottish genealogists, traced only one instance of the name before 1700. That reference, dated 1670, was to a James Barles in West Cultmalundie in Tibbermore parish, just west of Perth. Obscure though the name clearly was, it at least had some currency in the south-east of Perthshire in three generations before George Gilfillan’s mother, with post-1700 examples occurring at Mill of Gartly and Foulis Wester, both close to Crieff. In 1702, a Margaret Barlass, widow of Andrew Whyte, baillie of Perth, possessed various properties around the burgh, and infrequent references through the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries suggest that a minor network of families of that surname did exist in Perth and the surrounding parishes.

Catherine Douglas bars the door for King James I

None of the multiple histories of Perth published in the century after Scott contains anything other than the straightforward Catherine Douglas version of the tale

So, Barlass / Barlas was a name with a history in Perthshire since at least the seventeenth century, but it had no register in the historical record at anything above the extremely local scale. Gilfillan apart, no authority with a more than local influence made any reference to the story and, possible family tradition apart, there seems to be no more solid evidence to support his claim. Where most mainstream national histories failed to make mention of the Barlass tale, despite the identifiable presence of a family with that surname in south-east Perthshire, contemporary local histories are equally reticent, although Andrew Jervise’s 1861 Memorials of Angus and the Mearns was apparently the first to identify the error in Boece and offer the true names of the husband and wife in the Lovel of Ballumbie marriage. Strikingly, none of the multiple histories of Perth published in the century after Scott contains anything other than the straightforward Catherine Douglas version of the tale. If the Barlass tradition was current within that family, it was certainly not circulating any wider amongst the antiquarian networks of Perth and district. That position was to change dramatically in the 1880s.

In the second part of this blog, I shall explore the emergence of the Catherine Douglas/Kate Barlass legend and its embedding into mainstream literary discourse and artistic representation through the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Featured Image: Catherine Douglas Barring the Door c1910. Artist: Unknown

Images: Public Domian