Kate Barlass – Catherine Douglas

History, Myth and Modern Folk Tale

Part 2

Victorian Literature and the Making of the Modern Kate Barlass

Professor Richard Oram

Following George Gilfillan’s publication in 1860 of Specimens with Memoirs of the Less-known British Poets most academic and antiquarian histories remained silent on the question of the Catherine Douglas/Kate Barlass equivalence. Drama and literature, however, proved to be more fertile breeding grounds for ever more elaborate romantic interpretations. The earliest large-scale endeavour in this regard had been the 1843 play Catherine Douglas: A Tragedy, written by the civil servant Sir Arthur Helps. Outstanding only in its awfulness, Helps played fast and loose with historical accuracy in an effort to produce a work of high drama. Rarely performed, it had been almost forgotten by the end of the nineteenth century.

Far more successful was Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s epic 1881 poem, The King’s Tragedy, which reached a wide audience in late Victorian Britain. The subject matter of the poem was ideal material for Rossetti, who was one of the leading figures in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a cultural/artistic group whose members included other eminent artists like John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt. Medieval romances and Arthurian legends provided rich imagery for many of their paintings, but Rossetti was equally talented as a poet and wrote epic poems in the vein of medieval romances. His correspondence with his brother carried out over the time he was writing The King’s Tragedy, reveals that he was familiar with Gilfillan’s Specimens and his reference to the Barlass surname. He asked his brother to check Gilfillan’s reference for ‘I can find nothing about Barlass elsewhere…’. By ‘elsewhere’, Rossetti meant in other histories, for he had checked the recently published eight-volume History of Scotland by John Hill-Burton, which he had in his personal library. There is no hint in their continuing correspondence that any further mention of the name was found by either Rossetti brother.

It was from Gilfillan that Rossetti took the idea of Catherine Douglas becoming Kate Barlass

Modern analysis of Rossetti’s poem has shown that in addition to Gilfillan he had access to a copy of James’s own poem The Kingis Quair, to one of the various editions of Shirley’s account that was then in circulation, to the 1821 printing of Bellenden’s translation of Boece, and to Scott’s Tales of a Grandfather. All of the ingredients were drawn together from this rich collection of sources, with several new strands introduced to add to the drama of the events being described within his poem. There are errors, principally in Rossetti’s mistaken identification of the Blackfriars’ monastery in which James perished as the Carthusian Charterhouse in which he was buried, and the discrepancy of two Douglases – Elizabeth and Catherine – remained unresolved. New dimensions were added, principally the supernatural themes that were progressively worked up from a blend of the Shirley and Boece accounts with the somewhat florid prose of the Reverend Gilfillan. Finally, it was from Gilfillan that Rossetti took the idea of Catherine Douglas becoming Kate Barlass.

The four opening stanzas to the poem establish immediately the identity of Catherine / Kate and the part played by her strong arm in the tragedy of King James I:

I Catherine am a Douglas born,

A name to all Scots dear;

And Kate Barlass they’ve called me now

Through many a waning year.

This old arm’s withered now. ‘Twas once

Most deft ‘mong maidens all

To rein the steed, to wing the shaft,

To smite the palm-play ball.

In hall adown the close-linked dance

It has shone most white and fair;

It has been the rest for a true lord’s head,

And many a sweet babe’s nursing-bed,

And the bar to a King’s chambere.

Aye, lasses, draw round Kate Barlass,

And hark with bated breath

How good King James, King Robert’s son,

Was foully done to death.

After narrating the background to James’s reign, from his flight into exile in 1406 and long imprisonment in England until 1424, down to the siege of Roxburgh in 1436 and Robert Graham’s attempted arrest of the King in parliament, the poem’s heroine described the Highland seeress’s attempts to warn James of his approaching doom. The scene thus set; she moved on to explain why she was no longer known as Catherine Douglas:

And now, ye lasses, must ye hear

How my name is Kate Barlass: —

But a little thing, when all the tale

Is told of the weary mass

Of crime and woe which in Scotland’s realm

God’s will let come to pass.

Through the description of the last evening in the chambers at Blackfriars, it is Catherine who is the principal figure in attendance on the royal couple. When the assassins are heard approaching, it was she and Queen Joan who sought to help the King escape, Catherine being the one who thrust into his hands the tongs with which he prised up the floorboard to let him down into the closet below. It was Catherine to whom Joan turned to try to secure the door:

Then the Queen cried, ‘Catherine, keep the door,

And I to this will suffice!’

At her word I rose all dazed to my feet,

And my heart was fire and ice.

Going to the entrance to the royal apartments, she found nothing with which to bar the door and was faced with a desperate choice between using her arm or allowing the assassins to enter freely:

And now the rush was heard on the stair,

And ‘God, what help?’ was our cry.

And was I frenzied or was I bold?

I looked at each empty stanchion-hold,

And no bar but my arm had I!

Like iron felt my arm, as through

The staple I made it pass: —

Alack! it was flesh and bone — no more!

‘Twas Catherine Douglas sprang to the door,

But I fell back Kate Barlass.

The King’s Tragedy had broadcast the story and given it an audience on an international scale

Although critical opinion of the poem at its 1881 publication in Rossetti’s Ballads and Sonnets was decidedly varied, it had a profound impact on the reading public and over the next forty years sparked an outpouring of further literary and historical interpretation. For several decades, large sections of the poem were used as word-illustrations for popular histories, which provides clear evidence for the impact of Rossetti’s work amongst at least the non-academic historical writing community. It also inspired a new wave of artistic interpretation that was to provide some of the most memorable visual images in modern accounts of the King’s death. Unfortunately, it failed to trigger much deeper historical research into the origins of the Catherine Douglas/Kate Barlass story. Writing little over a decade after the publication of Rossetti’s poem, the French scholar Jean Jules Jusserand, whose history of James I was translated into English in 1896 as The Romance of a King’s Life, could observe that ‘the famous deeds of the “bar-lass”’ were ‘the best known, but the least certain’ of the events of the reign and that contemporary accounts were silent as to her role, if any. He did not, however, seek to delve any deeper himself.

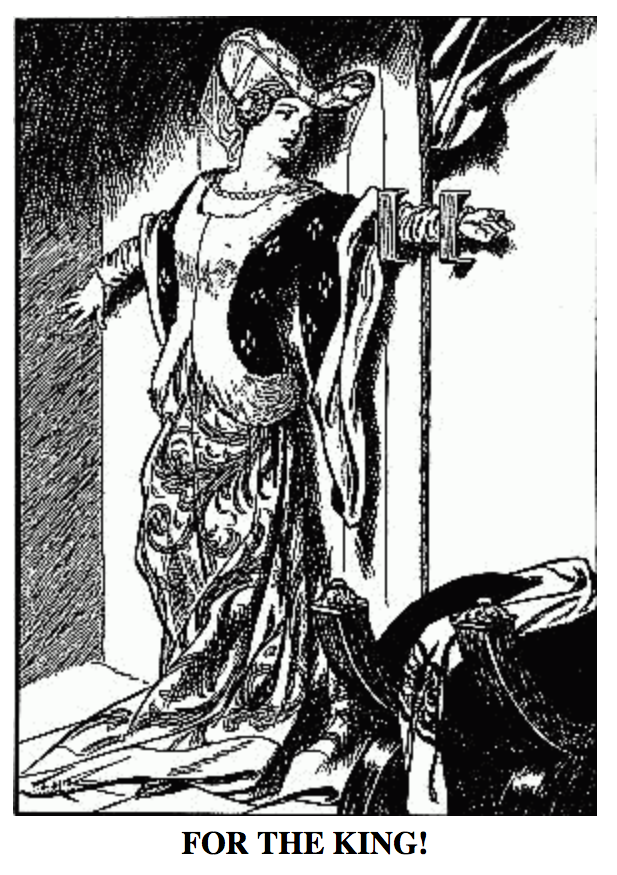

The King’s Tragedy had broadcast the story and given it an audience on an international scale, sparking scholarly interest in the tragic life and death of the poet-king. It was, however, to be in a new wave of historical writing – and the artwork commissioned to illustrate it – that the enriched narrative created by Rossetti found its most fertile ground. A decade after the poem’s publication, Gordon Browne produced a dramatic visual rendering of the scene for the Reverend Thomas Thomson’s multi-volume A History of the Scottish People, published in 1893. Although the good Reverend’s distinctly plodding text makes no direct mention of the Kate Barlass story, the account of the assassination he offered is clearly influenced by the same sources as informed Rossetti.

Catherine Douglas – Gordon Browne

A History of the Scottish People (1893)

Browne’s accompanying image, however, is even more strongly based upon the poetic vision and it seems that a level of wider public knowledge of the events of February 1437 was assumed to exist by the painter. He lifted his imagery directly from The King’s Tragedy: here is the gorgeously attired royal lady-in-waiting, her outstretched arm thrust through the bar staples of the door, face set in determined resolution. At her feet, pressed against the door, is a second female figure with a drawn dagger. The air is one of tense anticipation of the violence to come rather than of the explosion of violence that followed, and it was the format followed in subsequent renderings of the scene.

Thomson’s History of the Scottish People was aimed at educated adults, but others of the new wave of writers inspired by Rossetti and the romantic vision of Scotland’s story sought to cater for a younger readership.

Kate Barlass – J.R. Skelton

A history of Scotland for boys and girls by Henrietta. E. Marshall (1907)

Amongst the most influential of such new literary accounts was a volume of tales from Scottish history produced specifically for children. Henrietta Marshall’s 1907 publication, Scotland’s Story: A History of Scotland for Boys and Girls, beautifully illustrated by artists including Joseph Skelton, remained a staple of Scottish Primary School libraries into the 1960s. Marshall’s text is liberally laced with extracts from Rossetti’s poem, leaving no doubt as to the source of much of her inspiration, but she drew as heavily on Sir Walter Scott’s Tales of A Grandfather. Catherine Douglas is very much the heroine of the narrative, who tried desperately to keep the assassins from entering the room while all of the other women cowered in fear. ‘But one brave lady […] stood by the door, her arm thrust through the iron loops where the bolt should have been. She at least would what she could to keep the traitors out’. Skelton’s supporting illustration, clearly influenced by Browne’s, is often reproduced and as frequently imitated or parodied. It shows a decidedly robust young woman of athletic build holding shut the door, round the edge of which the points of bladed weapons have pierced. ‘Brave Catherine tried in vain to keep them back. They broke her pretty white arm, and rudely threw her from the door as they burst it open and dashed in. Ever afterwards, Catherine was called Catherine Barlass, because of her brave deed’. For the next two generations, the very particular image of the heroine presented by Browne, Marshall and Skelton was reinforced in children’s imaginations.

Catherine Douglas Barring the Door – unknown artist (1910).

Fast on the heels of the Skelton painting came several even more dramatic representations of the scene. Amongst the first was an anonymous 1910 print produced for the Pictorial Record of Remarkable Events in the History of the World, which borrows heavily from Skelton’s interpretation. Here, a somewhat languid, even bored-looking Kate Barlass has her right arm barring a door, round which clutching fingers and bladed weapons are intruding.

Kate Barlass – Golden Book of Famous Women

Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale (1919)

By way of contrast, the lady-in-waiting in Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale’s depiction, painted in 1919 for her lavishly illustrated publication, Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale’s Golden Book of Famous Women, is tense and fearful yet determined. The book’s subjects were a series of major female figures from history, historical fiction or theatrical dramas, many with strongly Christian religious associations (for example, St Catherine of Siena, or Heloise of the Abelard and Heloise love story). Whilst most are explained in conjunction with a long prose text extract, Fortescue-Brickdale’s Kate Barlass has a single stanza from Rossetti’s poem and the striking painting of her in much the same pose as Skelton’s heroic Kate. Fortescue-Brickdale’s Kate, however, is significantly slenderer and her arm far more fragile looking than Skelton’s muscular Brunhilde! Targeted at middle-class young ladies of a possibly Suffragist persuasion, the book was a celebration of powerful, inspirational and only occasionally tragic women, offering a counterbalance to the standard fare of (male) ‘Heroes of Empire’ products that catered for the young teenage male equivalents.

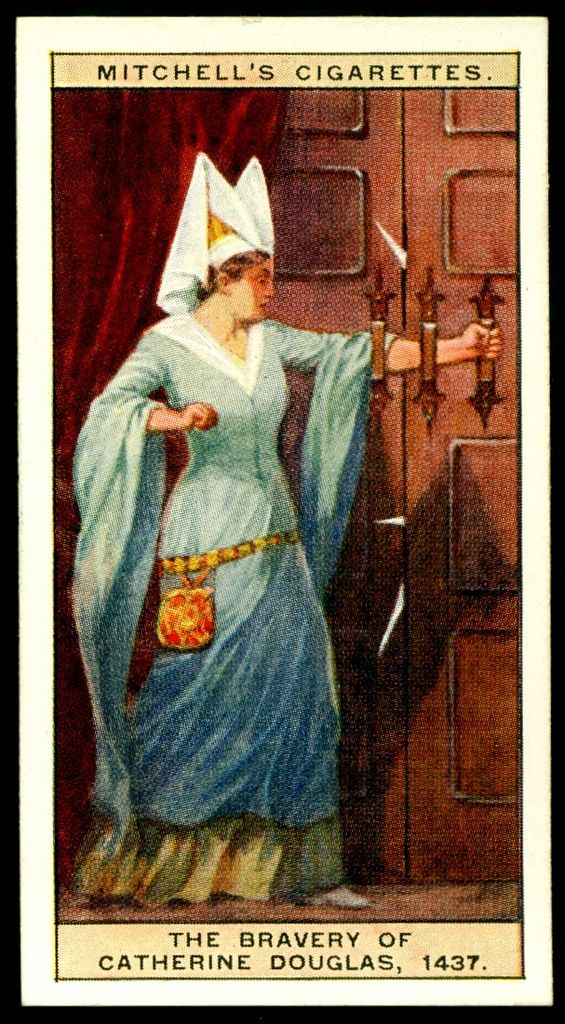

The Bravery of the Scots

Mitchell Cigarettes card series – unknown artist (1929)

It was males, however, at whom the 1929 image of a lone Kate holding closed the door against the armed threat outside was largely aimed in the anonymous painting produced for the Mitchell Cigarettes card series, The Bravery of the Scots. In the new Scotland of the post-World War One and post-1928 Representation of the People Act era, female heroism was to be praised and promoted on the same terms as male acts of bravery. And not just celebrated but actively popularised, for these card series, collected avidly by the children of the nation’s smokers, were one of the most powerful unofficial media for dissemination of knowledge and learning, alongside the growing portfolio of informative comics and magazines aimed at children and young adults.

Through these multiple strands of literary and visual depiction, half a century after Rossetti’s poem, reinforced by successive waves of popularised representations, his vision of the Katherine Douglas story had become embedded in non-academic popular histories of Scotland. Amongst the most influential of these was the lecturer and educationalist Agnes Mure Mackenzie’s 1935 volume The Rise of the Stewarts, where ‘Katherine’ Douglas featured prominently as a brave but somewhat ineffectual delayer of the assassins. The whole narrative of events from the prophecy of the Highland seeress through to the bloody end of Robert Graham and his accomplices provides the context for the brave lady-in-waiting and, although the mythic possibility in the story is alluded to by an aside that ‘they say’ that she had attempted to slow the assassins, she is given equal historicity with Christopher Chambers, Robert Stewart, Robert Graham and Walter of Atholl. Even though academic cold water was poured on the tale the following year when Evan W M Balfour-Melville published what was for the next sixty years to be the definitive academic political biography of the King in his James I, Mackenzie’s popular account of the king’s death helped to fix the Kate Barlass legend firmly in the public consciousness across the middle decades of the twentieth century.

Through Tranter’s Catherine Douglas, we are introduced to the high-minded, loyal, moralistic, self-denying and deeply principled man beneath the crown

And there it has remained. Academic caution, such as expressed in Michael Brown’s 1994 monograph James I, has made little impact on the popular reputation of the king’s legendary defender. If anything, the tale has grown ever more complex as further layers of fantasy and fiction are interleaved with the mistaken image produced by Boece five centuries ago. An important contributor to this continued embellishment was the fictional character built up from the bare bones of the medieval narrative by the novelist and popular historian, Nigel Tranter. His 1967 novel Lion Let Loose, which offers a very fanciful version of the events of 1402 to 1437 from the personal perspective of the King, introduces Catherine Douglas as a voluptuous, glamorous potential love interest for his moody, introspective and romantically idealist James.

From the first she was used as a device to introduce a sexual frisson into a James-Joan-Catherine triangle

Tranter resolved the Elizabeth / Catherine identification problem by making them two separate women, both ladies of the queen and both of whom would ultimately play a part in the events of 20/21 February 1437. Tranter’s Catherine is introduced early into the narrative, being with the royal household from the 1420s, and from the first she was used as a device by him to introduce a sexual frisson into a James-Joan-Catherine triangle. Tranter’s Catherine is a classic character of the ‘bodice-ripper’ genre, in his words ‘a tall and strapping well-made wench’ whom we first meet dancing with ‘flagrant lustiness’ in the courtyard at Linlithgow. With her gown ‘kilted well above her knees and her bodice … slipped from her fine shoulders, completely uncovering one of her jouncing and magnificent breasts that glowed extraordinarily more white, save for the nipple’, she oozes femininity and is presented as potently seductive, even when she was later offered to James for ‘companionship’ by the pregnant Queen Joan. Moral and idealistic to the last, James declines the offer, but in such a gallantly apologetic way as to ensure Catherine’s continued devotion to him. That devotion led her to seek to protect James as best she could and, to heighten the drama, Tranter added scenes with the injured Catherine attempting to aid the wounded Queen and further impede the assassins, despite her broken arm. Tranter’s treatment makes the cardboard cut-out heroine of the nineteenth- and earlier twentieth-century popular history into an altogether more complex and – no pun intended – well rounded character. For all her new humanity, however, she remains a fictional character whose personality has been constructed to enable the author to explore the aspects of James’s personality that he wanted to stress especially. Through Tranter’s Catherine Douglas, we are introduced to the high-minded, loyal, moralistic, self-denying and deeply principled man beneath the crown, the absolute antithesis of the greedy and vindictive ruler of fifteenth-century tradition.

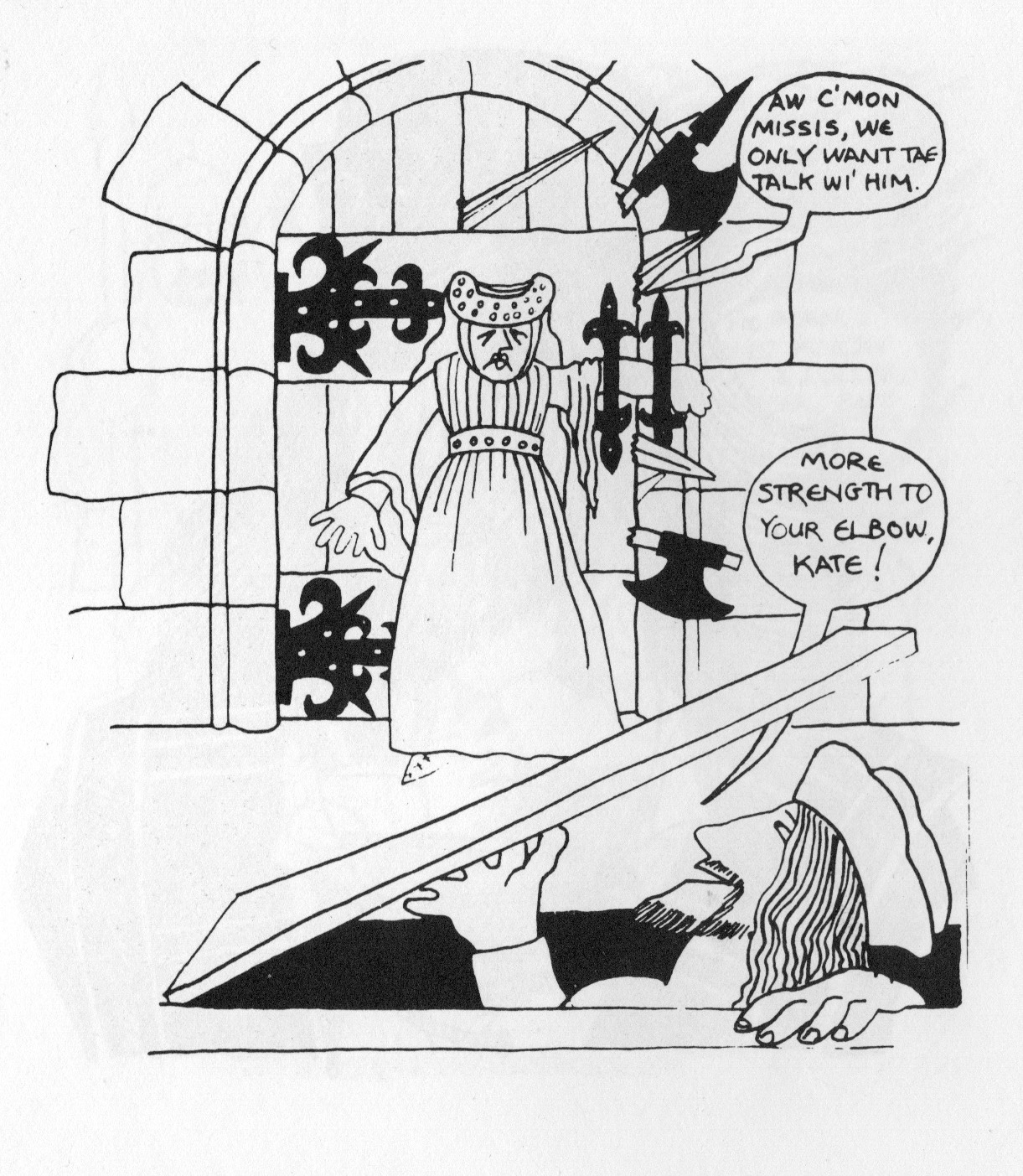

Kate Barlass – Scotland Bloody Scotland

Baron of Ravenstone (1986)

If Tranter’s 1967 Catherine/Kate represents the sublime, The version is the almost ridiculous. Set amidst a canter through the history of Scotland Bloody Scotland, a narrative that ranges from the mawkish and mistaken to the insightful and inspirational, a succession of cartoon images illustrates key events in the nation’s development from the Neolithic to the Union. Despite going to a second edition in the early 2000s it is now a little-known examination of the Scots’ psyche. Irreverent and tongue-in-cheek whilst making a serious point, Scotland Bloody Scotland formed part of the post-1979 failed first effort at Devolution navel-gazing at Scotland’s future through reflection on its past. There is much negativity, culminating in the Baron’s observation that Scotland’s own people are the only thing holding it back from achieving its place as a self-determining nation, but much too for celebration. Much of the narrative builds towards the somewhat bleak conclusion, but amongst the bright spots was the reign of James I, who is given one of the most extensive treatments in the whole of the slim volume. It extols his virtues and his efforts to make the kingdom strong, lamenting his bloody demise in the nobility’s reaction against his endeavours.

Aw c’mon Missis, we only want tae talk wi’ him

His assassination is illustrated with a drawing – clearly parodying the nineteenth-century images of Kate Barlass – of a pained-looking lady with her brawny left forearm thrust through the draw-bar staples of a door around the edge of which bristle an array of axes, swords and halberds. A smiling James in the foreground is lowering a hatch as his sinks into blackness below, calling out ‘More strength to your elbow, Kate!’ as he goes, while from outside the room comes the call ‘Aw c’mon Missis, we only want tae talk wi’ him’. For the Baron, this Kate Barlass was no less real than James himself, being the only party in the events of 20/21 February other than the king to be named in the supporting text. There is no excusatory label of tradition added to the tale; she is presented as a real, historical figure. With few heroic men or women visible in late twentieth century Scotland to be lionised by the Baron – who saw no point in detailing the nation’s experience from 1707 to his present – he, like so many Scots of the time, made do with mythic figures from a more glorious past that could be repurposed and reframed to fit the needs of the time. The Baron’s Kate Barlass is hardly Mel Gibson’s Wallace, but the underlying intention was the same.

Catherine Douglas barring the door with her arm – Werner Laurie (1910)

Illustration for Tales of a Grandfather by Sir Walter Scott

The late twentieth-century literary treatment of the Kate Barlass story and the heroine at its root is simply the culmination of the trend that is most marked in pictorial renderings of the story; the wonderful plasticity of the simple character sketch first laid out by Boece and the ease with which she could be adapted to the spirit of the age. The paintings and sketches that were produced with increasing frequency from the 1880s did not just offer a ‘Kate’ who conformed with the idealised – usually male rendered – female beauty of their time but they also linked her to the changing social place of women. Catherine Douglas, completely obscuring the historical figure of Elizabeth Douglas, moved from a supporting role in a story dominated by three male figures – the King, Robert Graham, and Atholl – and the quasi-male figure of Queen Joan (who took on the male role of avenger of the slain King) to one where she alone occupied centre stage, with James and Joan often reduced to shadowy background figures. This shift was already evident in the work of Gordon Browne, Joseph Skelton and Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale produced over the three decades after 1890. Browne depicted his Kate as just the boldest of the two ladies whom he portrayed as guarding the door, with Skelton’s royal couple reduced to out-of-focus and vaguely ghost-like figures in the dimly-lit inner chamber, while Fortescue-Brickdale’s Kate was the only figure in the scene. Many other renditions could be added to this list, like Werner Laurie’s c.1910 image for a new edition of Scott’s Tales of a Grandfather in which the striking yellow-clad figure of Kate dominates the four female figures behind her who are clustered around the pathetic, retreating figure of James, who is reduced to a fear-filled face and one claw-like hand disappearing into his hiding-place. Arthur A. Dixon’s 1930’s Kate is even more dominant, with just three women in the background around the hole in the floor, with no trace of the King.

Katy Barlass – Chris Rutterford (2017)

Visual reimagining has continued to the present. The most recent example is the dramatic rendering of ‘Katy Barlass’ painted in 2017 by the former comic-book artist and leading Scottish muralist Chris Rutterford, whose bold style captures the drama and violence of the assault on the royal chambers in the Blackfriars monastery. Here, however, unlike the defiant, heroic figures of the twentieth-century portrayals, Kate is depicted as desperate and suffering, her face a contorted grimace and her arm shown twisted and bleeding as clutching hands and hungry faces peer through the widening gap of the doorway. Behind her, the small figure of James (a re-used sixteenth-century portrait of the King), looks vaguely shocked as he pops through the trapdoor in the floor. There are no other figures in the painting. It is still the legendary figure of Boece’s creation, but she is once again humanised and made frail and ‘damaged’, with all of the posturing and pristine beauty of the previous century stripped away. Here, while Kate remains the central figure in the story being presented, that story has returned from the almost sterile stage sets of the Browne, Skelton and Fortescue-Brickdale style to the bloody reality of John Shirley’s fifteenth century Dethe narrative. Rutterford’s ‘Katy Barlass’ is a vision of pain, terror and bloodshed, and in that it comes closest of all the pictorial renditions to date to the reality of James’s brutal murder.

Even in Perth, the epicentre of the legend, there was no pre-twenty-first-century commemoration in song

It is striking that for all the literary representations and visual depictions of Catherine Douglas/Kate Barlass, the one artistic medium in which she is almost wholly unrepresented is music. This virtual absence is probably to be explained by the late date at which the legend became popularised, long after the era in which balladry would have been one of the most powerful media for spreading the tale. Even in Perth, the epicentre of the legend, there was no pre-twenty-first-century commemoration in song. It was only in 2014 that Catherine Douglas received musical treatment in a song by Perth-born singer-songwriter Eddie Cairney, who described himself as being brought up on stories of the Battle of the Clans on the city’s North Inch, the Fair Maid of Perth and, of course, Catherine Douglas/Kate Barlass. The song ‘Catherine Douglas’ was written as part of his album A Brief History of Scotland in Song. The album spans Scotland’s story from St Columba to the present and, like Cairney himself, is strongly nationalist with a strong forward-looking message with positive questions around the nation’s future potential. Although there are more than a few ‘great men’ figures in the narrative that unfolds through the songs, the over-all focus is on the more ‘ordinary’ men and women who shaped Scotland through their actions and aspirations; it is on such people, is the album’s message, that Scotland’s future continues to rely. Cairney’s Catherine Douglas is presented as a contrast between the faithfulness and loyalty of one ordinary woman to the faithlessness and treachery of Robert Graham and Robert Stewart, ostensibly her social betters. Whether you hear in that a political metaphor for Scotland’s current state or take it prima facie as a representation of the human frailties that underlie the historical reality, it presents us with a powerful message.

Catherine Douglas and the legend of Kate Barlass

Eddie Cairney ©2015

Verse 1

Catherine Douglas was a bonnie lass

True tae her ain’ Scottish Laird

She wad gladly gein her life that day

For that lass she wis’na fear’d

Verse 2

Skulkin’ in the street outside the hoose

Where the King and Queen did sleep

Robert Graham was wi’ his murderers

Treacherous vigil they did keep

Verse 3

Then they made their move their cowardly move

On their poor defenceless King

Robert Stewart had taken out the bolt

T’let the sleekit band move in

Refrain 1

Servants cried all is lost

There’s madmen at the door

Catherine up and barred it wi’ her erm

T’let the King flee ‘neath the floor

Verse 4

But these brutes they had but scant regard

For the safety of the maid

They broke doon the door and smashed her erm

Like it was a loaf o’ bread

Verse 5

They searched but couldn’y find the King

So they thought he wis ‘ny there

But they a’ got telt on their way oot

He is doon beneath the flair

Refrain 2

King James didn’y stand a chance

His foes were dressed tae kill

Though he fought them wi’ ee’s wrestlin’ skill

Their knives were better still

Verse 6

Catherine changed her name tae Kate Barlass

She did change it on that day

She would become pert o’ Scots folklore

For courage she did hae

From ‘A brief History of Scotland in Song’ released 2015

https://eddiecairney.bandcamp.com/track/catherine-douglas

It is the malleability of the Catherine Douglas/Kate Barlass figure that has perhaps ensured the triumph of the legend over the historical reality. That malleability has allowed her to be shaped to fit the spirit of the times, from the outrage of sixteenth-century writers who saw in her a lone figure standing up to those who breached all social, moral and political conventions through their bloody-handed murder of their true, God-anointed King, through those who saw her as an archetype of female bravery and defiance in the face of insurmountable odds, to those who saw her as the personification of the character of the Scottish people. In the almost six centuries since 1437, this ‘Kate for all seasons’ character has utterly displaced the actual human upon whom the legend is founded, Elizabeth Douglas. But, where so little is known of the historical personage, with no memoir, no ‘voice’ surviving, the fictional Catherine/Kate has given an obscure scion of two of the medieval kingdom’s great noble houses a vicarious afterlife. The further removed in time we are from the events of February 1437 and the deeper into folk tradition the Kate Barlass story has become embedded, the richer, rounder, more elaborate her tale has become, each new layer in the re-telling saying more about the needs of present audiences than the realities of the past.

Kate Barlass

Golden Deeds: Stories from History (Anonymous) The Project Gutenberg (2008)

Fearured Image: Katy Barlass by Chris Rutterford (2017)