The Clash of Swords and the Clash of Ideas

(Part 3)

The King who wrestled with his Lords and Philosophy.

Dr. Ray Scott Percival

James I was a formidable man, both physically and intellectually: he would with one blow dispatch you, and then compose a moving poetic obituary, and play a fitting dirge at your funeral. Later, he would play a game of chess whilst listening to au courant polyphonic music by John Dunstable. A lover of literature and poetry (inspired by Chaucer and Bower), an accomplished musician, and keen wrestler, James also wrestled with the abstract philosophical / theological narrative emanating from ancient Greece and North Africa – crucibles of intellectual work of the early medieval period.

12th and 13th Century trade routes

Information super-highways connected James to a flourishing network of knowledge

The trade routes, analogous to information super-highways, connected James to a flourishing network of knowledge, which was shaping the modern world. He was undoubtedly an advocate of this immigrant heritage and its potential – someone not easily ignored.

During his 18-year detention at the courts of Henry IV, V and VI, James was well educated and had ample access to the royal libraries. His poem, The Kingis Quair was stylistically influenced and dedicated to Chaucer, its content inspired by Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy (524 AD), acknowledged as one of the most influential philosophical works throughout the medieval period. Gibbon declared it ‘a golden volume’ and Bertrand Russell commented that…

It was as admirable as Plato’s The Last Days of Socrates.

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius (480–524 AD), a Roman nobleman and senator to one of the Gothic kings of Italy, Theodoric, produced translations of Aristotle and Plato, which ensured that at least some of these works were available throughout the west in the early Middle Ages.

Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, written during his own imprisonment, explored how philosophy could resolve such conundrums as evil men prosper while the virtuous die in poverty. His answer was that the prosperity of evil, if understood as fame, wealth, and power, was an illusion; true happiness is attained through seeking truth. Boethius puts fame in perspective by saying that since the world is infinite in time and space, it is of little account that one’s name – a mere label, and not oneself – is known for a thousand years.

He that to honour only seeks to mount

And that his chiefest end doth count,

Let him behold the largeness of the skies

And on the strait earth cast his eyes;

He will despise the glory of his name,

Which cannot fill so small a frame….

… Who knows where faithful Fabrice’ bones are pressed,

Where Brutus and strict Cato rest?

A slender fame consigns their titles vain In some few letters to remain.

Because their famous names in books we read,

Come we by them to know the dead?

You dying, then, remembered are by none,

Nor any fame can make you known.

Book II, Verse. VII.

At its time The Consolations of Philosophy was also the subtlest treatment of the problem of free will and God’s foresight: if God can see all of your choices in advance, in what sense are your decisions free?

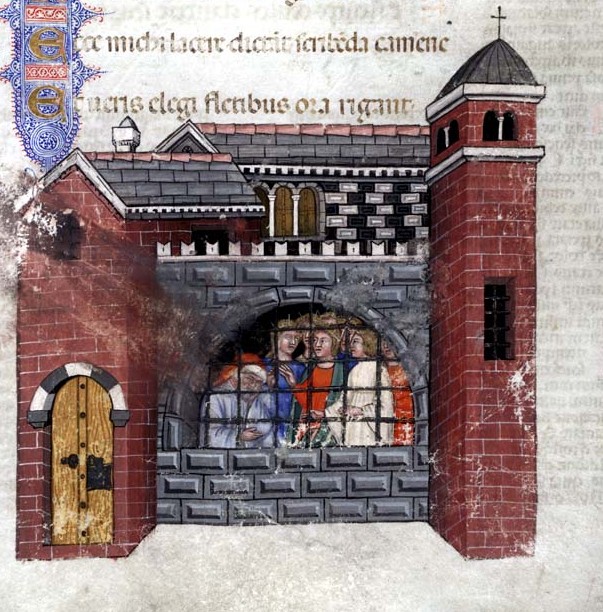

Boethius imprisoned: Consolation of Philosophy (1385)

James chose Minerva, the parallel Roman goddess of wisdom and an icon of The Renaissance

Boethius was imprisoned and sentenced to death on suspicion of being involved in a conspiracy against Theodoric’s government. In The Kingis Quair, the narrator (obviously a projection of James) is unable to sleep due to anguish resulting from his imprisonment, and begins to read Boethius’s account of his imprisonment in the Consolation of Philosophy. However, The Consolation of Philosophy is not what one would expect from Boethius, a devout Catholic facing martyrdom. Whilst drawing on the consolations of philosophy, it does not refer at all to the consolations of Christianity. It owes more to the Roman Stoic Seneca than to Jesus. In his reflections, it is interesting that Boethius chose Lady Philosophy as his mentor; James chose Minerva, the parallel Roman goddess of wisdom and an icon of The Renaissance. Just as Lady Philosophy counsels Boethius to a Socratic detachment from wealth and power and to embrace the love of wisdom, Minerva counsels James to seek wisdom.

James was fashioning Boethius’s work to his own design, and therefore became intimately acquainted with ancient Greek philosophy, its questions and conundrums

James was fashioning Boethius’s work to his own design, and therefore became intimately acquainted with ancient Greek philosophy, its questions and conundrums. The rational theology in Boethius’s work functioned, intentionally or not, as a Trojan horse for the spread of a freer ranging philosophy that was to pervade Scotland, and the wider western world.