The Clash of Swords and the Clash of Ideas

(Part I).

James I and the inaugural steps toward the Scottish Renaissance.

Dr. Ray Scott Percival.

Behind the clashing of swords and the blood-drenched fields of war, the intrigues, conspiracies, seizures of power and the rise and fall of empires, lies another deeper story: the growth of clashing ideas that govern peoples’ hopes, dreams, fears and action – the real governing power of societies.

Henry V of England – National Portrait Gallery, London

Although James I was capable of emulating the shrewd governance of his tutor, Henry V of England, he was a rash political strategist. He was not reserved about inviting Alexander McDonald, King of the Hebrides and Ross over to dinner – whose lands he coveted, promptly roughing up his family and men, and then throwing him in prison.

James was a conduit of critical theological and philosophical ideas that were emerging from Europe and which were transforming the intellectual culture of Scotland.

But there was another more sophisticated, promising side to James, and from his return to Scotland from England in 1424, until his spine-chilling assassination in 1437, James was a conduit of critical theological and philosophical ideas (in which his power was vested) that were emerging from Europe and which were transforming the intellectual culture of Scotland.

Popes Urban VI (left) and Clement VII (right)

James was born in a tempest. The rise of heresy, catalysed in the late 12th century by the foundation of autonomous universities and the massive influx of ancient Greek scholarly works into Christian Europe, and during his own lifetime, the Great (Papal or Western) Schism (1378 to 1417) – over what a modern observer might describe as the Monty Python-esque collapse of papal succession – with three contending elected Popes, one of which was a notorious ruffian rumoured to be an ex-pirate!

Council of Constance 1414

The council was to unify the church, bring an end to the schism in the papacy which had divided the church since 1378, eradicate heresies, and reform the corrupt morals of the church. (Chronicle of Ulrich von Richenthal).

It was James’s sophistication that held the promise that he might, for some, guide Scotland through this rising storm.

Scotland, along with the rest of Europe, was witnessing a massive decline in population due to a series of plagues, which were upsetting normal feudal relationships, because the ratio or scarcity of serf labour relative to land improved the bargaining position of serfs. It was James’s sophistication that held the promise that he might, for some, guide Scotland through this rising storm. But he was a King in a hurry, keen to systematically impose his rule on Scotland, stamping out heresy, endorsing institutions such as the University of St. Andrews, and creating laws designed to do just that – thus maintaining the hegemony of Augustinian orthodoxy.

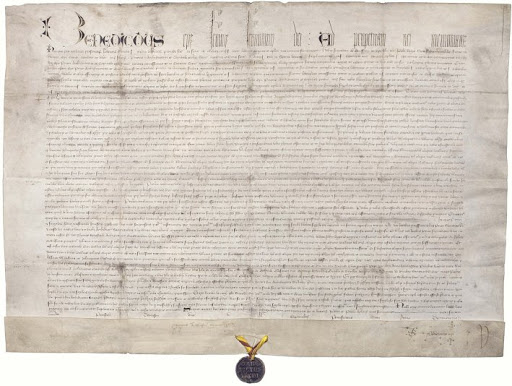

Papal Bull – University of St. Andrew’s.

Henry Wardlaw, Bishop of St Andrews, issued the charter of foundation in February 1411 and with James I’s consent the privileges of the new seat of learning were conferred, in return for Scotland’s loyalty, by a Bull of the Avignon Pope Benedict XIII on 28 August 1413. The university was to be an impregnable rampart of doctors and masters to resist heresy – https://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/museums

The capture of power is a matter of conjecture and refutation,

trial-and-error.

In retrospect, it’s easy to say he was heavy-handed and rash, but on the other hand, in a prudential sense, he was doing the right thing. How else can a de re King find out if he is de facto King? He could have consulted his advisors and listened carefully to the gossip (they didn’t have polls or Facebook-likes back then), but at the end of the day, the capture of power is a matter of conjecture and refutation, trial-and-error.

Ironically, the heresy that James sought to control was a product of the growth of reason throughout the Middle Ages.

James had to push and punch for that position to see if it met a counterpunch of equal or greater force – and James was to receive a plethora of counterpunches, leading, ultimately, to his tragic and dramatic assassination, and the collapse of the control of heresy. Ironically, the heresy that he sought to control was a product of the growth of reason throughout the Middle Ages that had shaped James’s own intellectual sophistication. It serves as a lesson in the futility of mind control.

Dr Ray Scott Percival – Philosopher and Author of The Myth of the Closed Mind and producer of the documentary Liberty Loves Reason.

Featured Image: Statue of Bishop Henry Wardlaw, founder of the University of St Andrews, the first university in Scotland, located at St. Mary’s College, University of St. Andrews, Scotland.