The Clash of Swords and the Clash of Ideas

(Part 2).

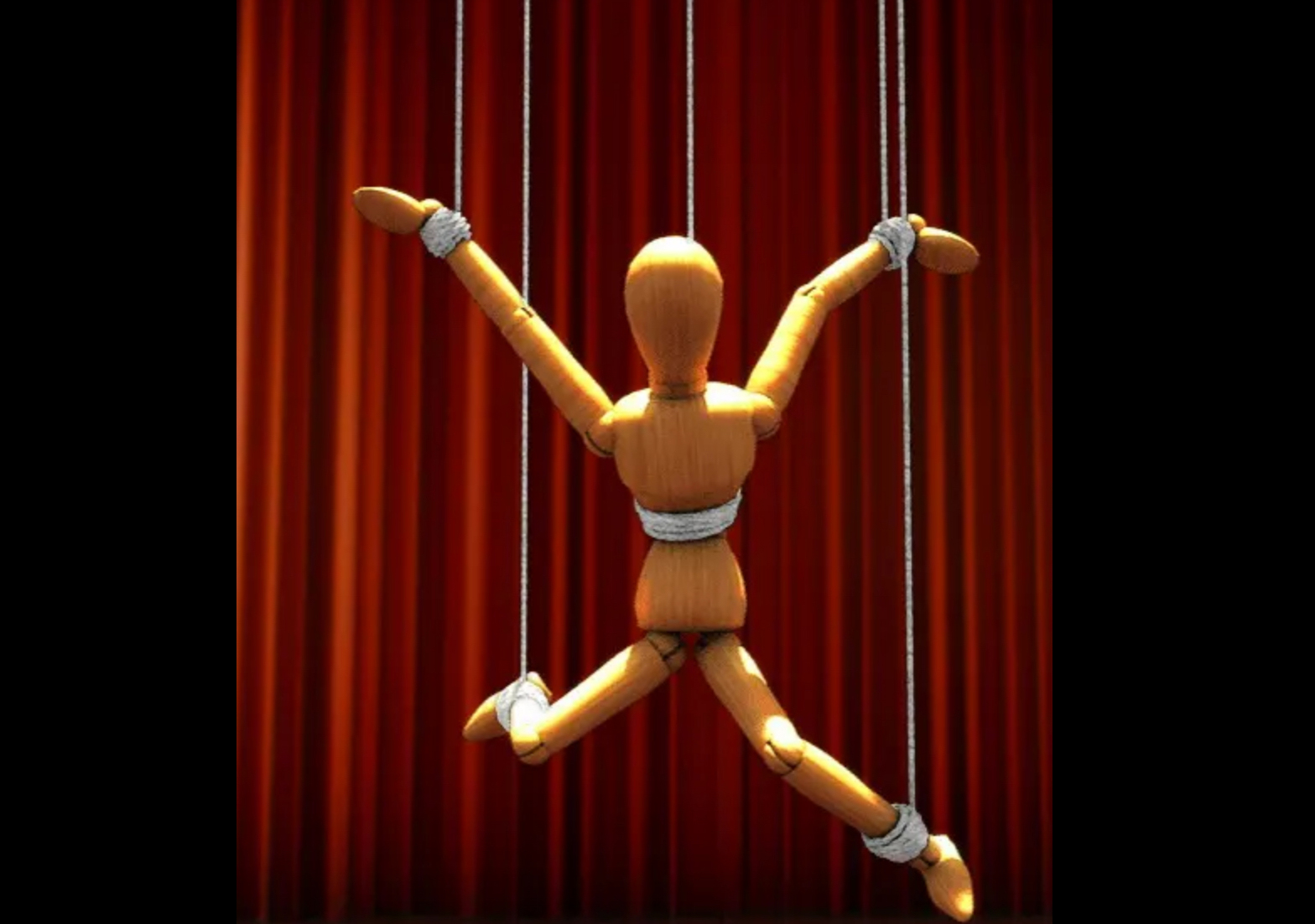

Pioneer and Puppet of Ideology.

Dr. Ray Scott Percival

Leaders introduce novel concepts to their society, but those must function within the perspective moulded by earlier scholars. James I, cultivated at the court of Henry IV and V in European-style rule and philosophy could have been more like David I before him – a pioneer and shrewd ruler, sensitive to the intellectual climate, especially that manifested within the Augustinian and other monastic orders. Building on Alexander I’s European ecclesiastical reform of the Scottish church, David I was adept at unifying the Gaelic highlands and lowlands, protecting the freedoms of religious groups (thereby stimulating trade), founding a myriad of monasteries, and in 1140 at St Andrews a Cathedral Priory of Augustinian canons. (Oram 2008, 156.)

St. Andrews Cathedral

James and his advisors (in particular, Bishop Henry Wardlaw) acted within, maintained, and reinforced such Augustinian influence. But, at the same time, James was scornful of what he saw as David I’s profligate spending on the churches; of David I, James said ‘that he was ane sair sanct for the croune’, and hastily imposed many unpopular intrusive restrictions on religious orders, for example establishing a Carthusian priory, the Perth Charterhouse, to provide other religious houses with an example of internal conduct. (Oram 2008, 2006.)

Scotland was more of a loose network of shifting allegiances of families, the McDonalds being among the largest of these.

James I’s reign was characterised by rash reform, badly tailored to Scotland’s cultural context, and driven along by a flood of unintended consequences of ideas developed throughout the Middle Ages that had acquired a life of their own. Although a wielder of power, this power was based, as for all sovereigns, on opinion.

David Hume

Scottish philosopher David Hume said:

‘Nothing appears more surprising, to those who consider human affairs with a philosophical eye, than the easiness with which the many are governed by the few; and the implicit submission, with which men resign their own sentiments and passions to those of their rulers. When we enquire by what means this wonder is effected, we shall find, that, as force is always on the side of the governed, the governors have nothing to support them but opinion.

It is, therefore, on opinion only that government is founded; and this maxim extends to the most despotic and most military governments, as well as to the most free and most popular. The sultan of Egypt, or the emperor of Rome, might drive his harmless subjects like brute beasts against their sentiments and inclination but he must, at least, have led his mamalukes, or praetorian bands, like men, by their opinion.

Of the First Principles of Government – Essay IV

You can imprison a lord, but not the opinion of his subjects

By ‘opinion’ Hume meant the opinion of right (legitimacy and social mores) and the opinion of interest (economic advantage). They are the unquestionable assumptions of the mass of the people in society: in James I’s day one would have been the legitimacy conferred by the Pope, underpinned by Augustinian theology; in our day (in western countries), we take for granted bureaucratic nation-states, underpinned by the theory of liberal democracy. In James I’s time nation-states, though incipient, did not yet exist. The nation as an ‘imagined community’ – to use Benedict Anderson’s phrase – was just a mere possibility: Scotland was more of a loose network of shifting allegiances of families, the McDonalds being among the largest of these. Family is a powerful social more, not to be ignored. James I imprisoned Alexander McDonald and got a hard lesson in the Humean theory of government because, ignoring the actual basis of Alexander’s power, he was defeated at Inverlochy when Alexander’s men from the Isles, and devoted to Alexander, routed the royal troops, killing nine hundred men. You can imprison a lord, but not the opinion of his subjects. James was to receive many hard lessons, and ultimately one that he could not learn from, his bloody assassination in the sewer under the Blackfriars Monastery, Perth.

These opinions change throughout the great sweep of history through the clash of ideas – generally as a result of a competition between highly abstract positions concocted by intellectuals, ideas that, like children of the mind, grow to have a life of their own, often frustrating the intentions and plans of their parents. (Dawkins 1976, Percival 2012).

Echoing Hume, but stressing the long-term and partly unconscious influence of ideas, Keynes said:

Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. I am sure that the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas.

Keynes, 1936, Section V, Chapter 24.

Arguably, Keynes’s famous assertion covers all the abstract belief systems produced by humankind that have engendered an ideology, doctrine or religion.

Featured Image: FBI.org