Pregnancy, Childbirth and Grief.

Tracing the Children of Margaret Tudor.

Amy V. Hayes

The Open University and the University of the Highlands and Islands

When Margaret Tudor arrived in Scotland in August 1503 she was thirteen years old. Even by medieval standards, this was a relatively young age for marriage and for the inevitable duty that lay before a queen – giving birth to an heir to the throne. In comparison, her groom, James IV was thirty years old. When her marriage was first proposed, Margaret was only nine, and both her mother, Elizabeth of York, and her paternal grandmother, Margaret Beaufort, objected to the idea of the young princess being sent to Scotland.

Margaret Beaufort had particular reason to be fearful

Margaret Beaufort had particular reason to be fearful for the health of her granddaughter as she herself had given birth to Henry VII, her only son, at the age of twelve. Both Margaret Beaufort and Elizabeth lobbied Henry VII against the Scottish match, with Henry VII stating that

‘the Queen and my mother are very much against this marriage…they fear the King of Scots would not wait but injure her, and endanger her health’.

This concern over Margaret’s health and wellbeing continued in the treaty arranged for her marriage; although she was married by proxy in January 1502, the treaty was clear that she would not be sent to Scotland until she was nearer the more ‘mature’ age of fourteen. In the event, Margaret’s journey north was three months short of her fourteenth birthday, to take advantage of travelling during summer rather than winter.

The consummation of her marriage was delayed

Even though Margaret arrived in Scotland in 1503 it is possible that the consummation of her marriage was delayed. This was not uncommon when young medieval brides were married. Often the couple might maintain separate households or simply avoid consummation until the bride was a more acceptable age – usually from the age of fifteen or sixteen. Margaret did not bear her first child until 1507, so it is likely that James IV respected this convention.

Whilst she was still young, she was effectively under the protection of her natal family

In addition, Margaret’s early household as queen of Scots was staffed by English attendants until 1506-7, at which point the majority left, and her household became more Scottish in terms of personnel. This staffing change links closely to Margaret’s first pregnancy suggesting that, whilst she was still young, she was effectively under the protection of her natal family.

Her first conception marked an appropriate time for Margaret to move fully into the position of adult queen

By 1506 Margaret was sixteen years old and considered an appropriate age for marriage and childbirth. Her first conception marked an appropriate time for Margaret to move fully into the position of adult queen of Scots rather than being in a transitionary role as a newly married foreign princess.

A queen’s ability to conceive and birth a male royal heir was of considerable importance to medieval society. Indeed, Margaret’s own sister in law, Catherine of Aragon, would be set aside largely because she and Henry VIII had been unable to have a surviving male child. Although Catherine of Aragon’s tragedy is well known, what is less acknowledged is Margaret Tudor’s own parental losses. After her first child was born in 1507, Margaret Tudor and James IV would go on to have another five children, of which only one survived to adulthood – the future James V, born in 1512.

If Henry VIII were unable to produce a legitimate son, it would be a son of Margaret Tudor, his elder sister, who would succeed

Margaret’s first pregnancy resulted in the birth of a male child, named James, in February 1507. This was clearly a cause for much celebration, and no expense was spared in caring for the young prince, but he died a year later in February 1508. At this point Margaret was already pregnant with a second child, a daughter whose name is unknown, and who was born and died in July 1508. In October 1509, a second son was born and named Arthur. This is a particularly interesting name, with links to the legendary King Arthur of the Britons, and may have been a deliberate ploy to remind the still heirless Henry VIII that, if he were unable to produce a legitimate son to succeed him, it would be a son of Margaret Tudor, his elder sister, who would succeed.

Chronicle accounts were less interested in short-lived female children than male children

The young Arthur died in June 1510, and Margaret’s next child, another daughter, was born around 1512-13, and who possibly died on the same day. Again, we do not know this daughter’s name – this may in part be because chronicle accounts were less interested in short-lived female children than male children, or it may reflect the fact that these infants died before their names could be recorded. Margaret then gave birth to the future James V on the 11th April 1512, and a final son, Alexander, was born in April 1514 after the death of his father at Flodden in 1513. Margaret was said to have been especially fond of Alexander, with one English commentator stating that,

‘her grace praiseth him more than she doth the king her eldest son’.

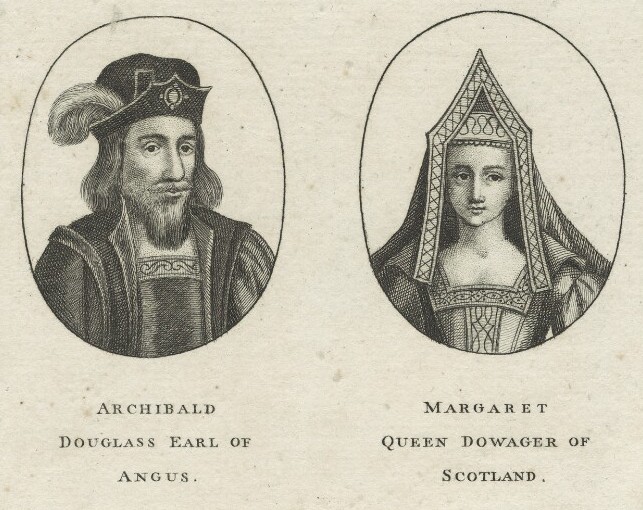

But the young prince died in December 1515. At this point Margaret was again pregnant with her only surviving daughter, Margaret Douglas, the child of her hasty second marriage to Archibald Douglas, earl of Angus, in 1514.

The toll that this almost endless round of pregnancy, childbirth and infant mortality took on Margaret must have been exceptionally difficult. As historians, we have now moved past the outdated notion that elite women did not have an emotional investment in their young children. The grief of Margaret, and indeed James, is traced in some chronicle accounts. For example, the royal couple are said to have travelled from Edinburgh to Stirling on the death of Prince Arthur and then remained there mourning him. When Prince Alexander died in 1515 Margaret was very ill after the birth of Margaret Douglas. Her companions made the decision to delay telling the queen about her youngest son’s death, as they feared the shock would kill her in her weakened state. Whatever Margaret’s illness was it seems to have prevented future conception, as the queen had no more children after 1515. She was at this point only twenty-five years old.

Margaret’s status as a mother was something she constantly referred to in her efforts to regain power

Margaret’s later pregnancies probably impacted on her ability to wield power in the early stages of the minority of James V. Although the queen was named tutrix of the young king and governor of the kingdom on the death of James IV, the queen was pregnant with her husband’s posthumous child throughout her brief period in charge. The impact of this sixth pregnancy in seven years has not been accounted for in considering Margaret’s failed regency, although she would have been forced to take a lying in period before and after the birth which would have restricted her ability to govern, even if the physical toll of medieval pregnancy and childbirth are not considered. Margaret’s status as a mother was something she constantly referred to in her efforts to regain power during the minority of her son, although she was unable to fully capitalise on this after James V was removed from her physical custody in 1515.

Margaret was also unable to raise her daughter, Margaret Douglas, who was taken by her father, the earl of Angus, and then raised at the court of Henry VIII.

Ultimately, the childbearing efforts of Margaret Tudor demonstrate the extreme vulnerability of medieval mothers, whose power rested in their ability to bear and raise children, but who were left on shaky ground when they could not exert custody.

Images:

James IV and Margaret Tudor, c. 1796, NPG D23903, © National Portrait Gallery

Archibald Douglass, 6th Earl of Angus and Margaret Tudor, c. 17th century, NPG D24242, © National Portrait Gallery

(creative commons)