A Fitting Funeral?

The Memorials of Margaret Tudor

Perin Westerhof Nyman

University of St Andrews

On 18 October 1541 Scotland lost its dowager queen Margaret Tudor, throwing her son’s royal household into mourning and triggering the flurry of work and preparations that necessarily accompanied a royal funeral. The queen’s body would have been embalmed and a vigil held, although direct details for this do not survive. The staff of the royal wardrobe presumably had to put aside much of their regular work to begin making the large quantity of mourning clothing ordered by the royal household. Messengers had to be sent out as soon as possible with news of the king’s mother’s death, and Perth Charterhouse, where the queen was to be buried, must have become the focus of a great deal of activity.

Margaret Tudor’s funeral has sometimes been presumed to have been underwhelming

Margaret was the mother of the reigning monarch of Scotland, James V, and sister of the reigning monarch of England, Henry VIII, and her status certainly demanded a splendid memorial. Yet her funeral has sometimes been presumed to have been underwhelming. James Balfour Paul, who edited and published the sixteenth-century royal Treasurer’s Accounts in the 1900s, expressed concern that the royal household’s purchases at the time of Margaret’s death did not record evidence of a sufficient or proper memorial having been held for her. Indeed, in the introduction to the eighth volume of these records, he stated that, beyond the provision of mourning clothing, ‘there is no other mention of the decease of one who played such a prominent part while she lived in the history of Scotland’ (p. xiii).

James IV and Margaret Tudor, eldest daughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York

Margaret certainly had played a prominent part in the early sixteenth-century history of Scotland. She had come to Scotland as an English princess, and the magnificent pageantry of her wedding to James IV (discussed in the first blog post of #MargaretTudorMonth) had celebrated an important political alliance. She had served as queen consort, and then as regent for her son, and she maintained her connections with both the Scottish and English courts throughout her life. However, due to chronic difficulties in collecting her incomes after James IV’s death, she seems to have struggled to maintain the material magnificence that she felt her station necessitated. She wrote to her brother on several occasions to request financial and material aid. For example, she took pains to point out that, as she was the sister of the king of England, her sub-par appearance, particularly at the major events relating to her son’s two French marriages, would reflect badly on the honour of England.

Portrait of Henry VIII after Hans Holbein the Younger, c. 1537–1547

This has contributed to the sense that this English princess and Scottish queen, who had arrived so magnificently in Scotland as a teenager and who was acutely aware of the importance of material splendour, had been so reduced in circumstances towards the end of her life – had become so shabby, perhaps – that even her funeral failed to properly reflect her status. As retellings of her brother’s exploits and decline have continued to fuel popular media and entertainment, this version of Margaret’s life and death has made for a compelling story. But does it hold up?

The royal household’s internal preparations reflected the expectation of a significant event

It is true that the initial payments for a funeral – the cloth of state, black hangings for the church, arrangements for the bearing of a coffin, and so on – are missing from the royal purchase accounts. However, it is reasonable to expect that these would have been paid out from Margaret’s own household, for which the accounts do not survive. Likewise, most of the initial payments and gifts of candle wax and fine goods that would have been made to Perth Charterhouse for the burial mass and ongoing prayers would normally have been provided for in the deceased’s will, or paid out from the estate. Thus, the fact that the royal household did not make these payments is not necessarily an indication that the funeral was insufficiently outfitted. Certainly, letters were sent out to invite the Scottish notables to the occasion, which may have taken place at the beginning of November, and the royal household’s internal preparations reflect the expectation of a significant event.

Although the royal household did not pay for Margaret’s funeral, they played central roles in the ritual display

In October and early November, the royal family and a number of their servitors all received ‘dule’ habits, or weeds: that is, a loose mourning gown of plain black wool, with a black wool hood that partially covered the face. These were worn for formal services, and the dule provided to the servitors was an extension of the royal family’s own mourning.

Portrait of James V and Mary of Guise, anonymous artist, c. 1542, at Falkland Palace

James V’s wife, Queen Marie de Guise, and her ladies also received black horse harnesses and riding equipment, presumably so they might participate in Margaret’s funeral procession, which likely carried her body through the main streets of Perth. Additionally, Margaret’s five ladies of honour appear to have been chosen from amongst Marie de Guise’s own household. Thus, although the royal household did not pay for Margaret’s funeral, they played central roles in the ritual display.

The royal apartments and chapel were entirely outfitted with black furnishings and hangings

The royal mourning for Margaret Tudor did not end there. Throughout October, November, and December, the royal family continued to receive only black clothing from the royal wardrobe. Moreover, the accounts for December show that a second memorial was held for Margaret, presumably accompanied by a full ‘dirge’ mass. For this occasion, further sets of formal dule weeds were provided to the royal family to replace those they had received just a month earlier; a significant further expenditure was made on black riding equipment; and the royal apartments and chapel were entirely outfitted with black furnishings and hangings, including four black wool cloths of state.

Margaret’s funeral was not a minimal or insignificant affair

Based on this evidence, Margaret’s funeral was not a minimal or insignificant affair, and it was not the only memorial she received. The whole season, from October through Christmas, spent in sombre mourning must have been memorable to those who observed the royal household during this period, or heard about the funeral from others. Some thirty years later, John Leslie – a bishop and historian who was in Scotland at the time of Margaret’s funeral, although he may not have attended personally – recalled that it had been an occasion of honour and pomp, worthy of note.

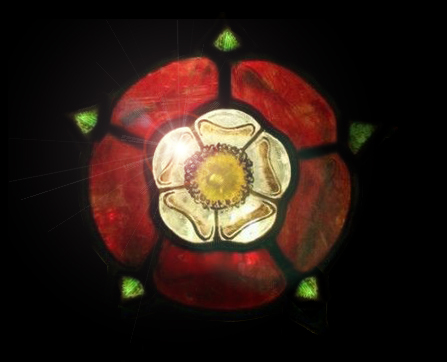

Margaret Tudor, Queyne – Stained Glass Window, Great Hall, Stirling Castle

It is unfortunate that no detailed descriptions or direct depictions of Margaret’s funeral survive. Yet it is clear that Margaret’s memorial, which closely involved her son and daughter-in-law, as well as much of the royal household, reflected the significant roles she had played as queen consort, mother, regent, and dowager over her nearly forty years in Scotland.

Featured Image: Codex Vindobonensis 1897 ‘Book of Hours of James IV of Scotland’, ca.1503, http://data.onb.ac.at/rec/baa18880732 /Austrian National Library

Portrait of Henry VIII – After Hans Holbein the Younger – Public Domain

Margaret Tudor, Queyne – Stained Glass Window, Great Hall, Stirling Castle © dun_deagh www.flickr.com/photos/dun_deagh/7302951396

Stained glass Tudor Rose © Paul Wilson