The Clash of Swords and the Clash of Ideas

(Part 6).

Religion creates its own Frankenstein monster.

The critical search via reason for universal laws of nature.

Dr. Ray Scott Percival

In his book The Victory of Reason, Rodney Stark conjectures that it was the Christian emphasis on a law-like structure to the world laid down by God that created the unique conditions in Europe for the rise of science as the search for universal laws of nature.

For these theologians the world was like a clockwork mechanism set off by the hand of God at creation; one could, therefore, figure out how it works, enhancing one’s understanding of God. In contrast, Stark says, Islamic thinkers, though outstanding contributors to specific areas such as medicine and astronomy, which did not require a general theoretical framework, tended to portray Allah as interfering at will with the flow of events, unconstrained by any invariant framework of physical laws. Besides, Stark argues, Islamic thinkers tended to take Aristotle as the last word in science. Other religions – such as Buddhism or Confucianism – were content to savour rather than analyse the mysteries of the world and were more concerned with knowledge of the self, proper governance and personal ethics.

Science was to become the major critic of all religions

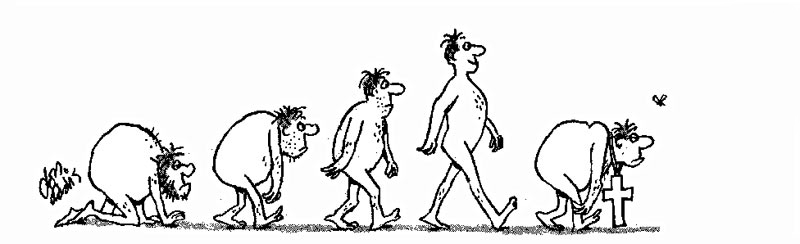

Stark’s thesis, I think, needs to be qualified. My main point is that reason and science, what was to become the major critic of all religions in the 18th Century (Voltaire), 19th Century (Darwin), and 20th Century (Russell), was growing throughout the medieval period within the very womb of Christianity.

Once created, the idea of universal laws, detached from its source, becomes an independent tool that could be put to other purposes. To qualify Stark’s thesis, we had to wait for Newton to see genuinely universal laws covering every object, apples, cannon balls, the Earth, moons, planets, comets and stars included; even Galileo’s laws of inertia, free-fall and the parallelogram of forces were confined to the Earth. (Percival, 2015.

Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night.

God said, ‘Let Newton be!’, and all was light.

(Alexander Pope).

It is customary to criticise, as does Stark, the dominance during the medieval period of Aristotle’s physics, but without Aristotle, there would have been no one for Galileo to topple; science needs clashing ideas for the better ones to emerge as tentatively triumphant. The emergence of science owes a debt to Islamic thinkers such as Averroes in boldly pushing Aristotle’s approach. Stark, like St. Augustine and Averroes, may have overlooked the fact that, once deployed, reason – not wedded to any particular ideas – can undermine its original purpose.

James I wasn’t a philosopher, being principally engaged in the strategy of power – the manipulation of what Keynes called ‘vested interests’ – through diplomacy, and violence

James I wasn’t a philosopher, being principally engaged in the strategy of power (the manipulation of what Keynes called ‘vested interests’) through diplomacy, intrigue and violence. Here, though, we might be critical of Keynes, since even how to categorise a ‘vested interest’ is not self-evident, but arguably requires some pre-existing conceptual framework and shrewd guesswork. However, the framework of James I’s thoughts had been moulded by this evolutionary development and clash of ideas.

James I was living at an exciting time of intellectual upheaval

Just as today most people take for granted parliamentary democracy, trial by jury and home insurance, so the people of James I’s era were imbued with their assumptions about what was considered right or correct ways to think about, and deal with, the world. They had their own, partly conscious, partly unconscious worldview. James I was living at an exciting time of intellectual upheaval.

Featured Image: A verger’s dream: Saints Cosmas and Damian performing a miraculous cure by transplantation of a leg. By: Master of Los Balbasesafter: Alonso de Sedano (1495). Public Domain.

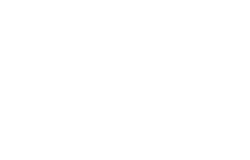

Blog images: Don Addis. An editorial cartoonist for most of his adult life, working for both the Evening Independent and the St. Petersberg Times in Florida, he contributed his artistic talents to many American magazines and also created three syndicated comics.