St. Mary’s Chapel.

Professor Richard Oram.

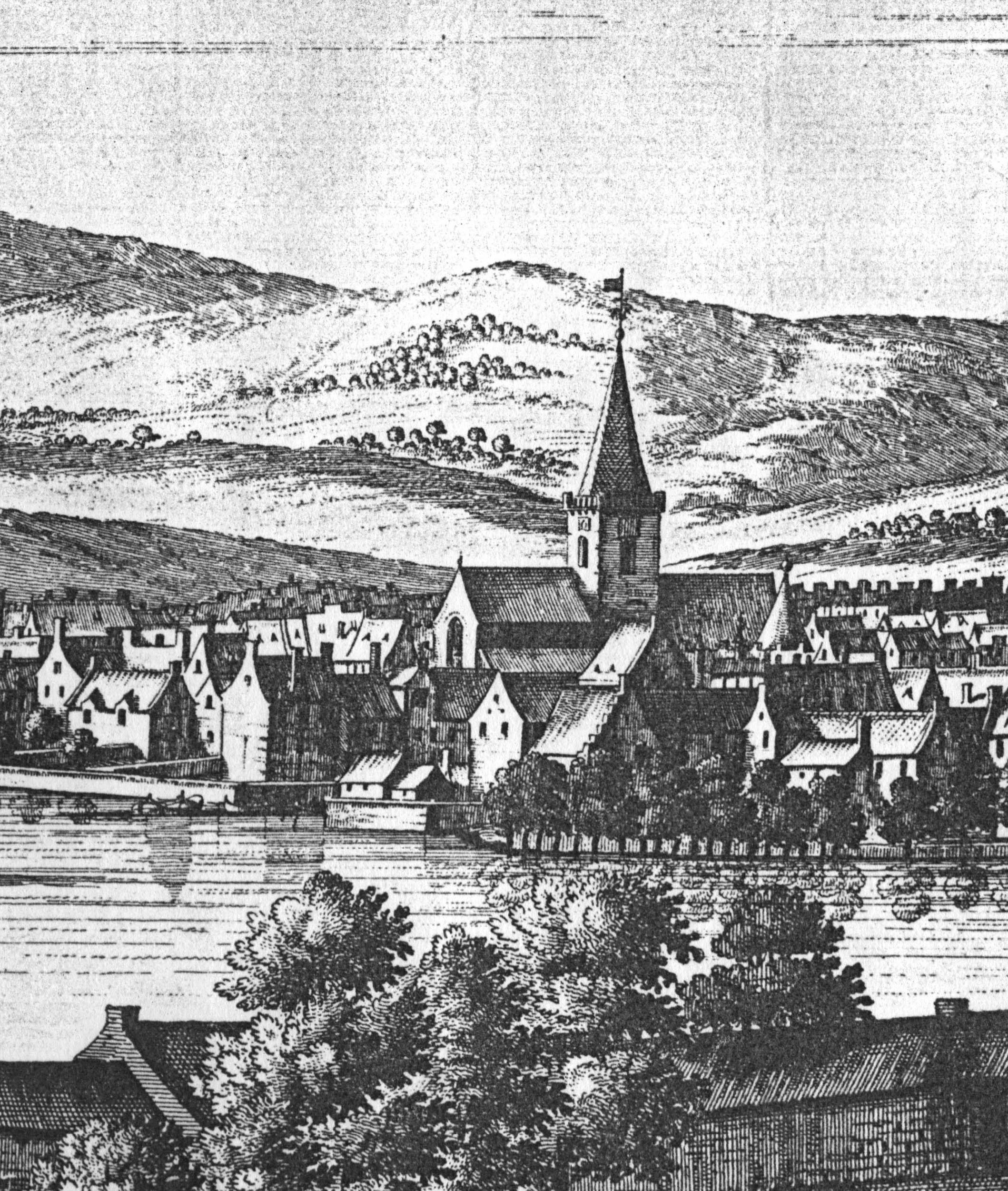

A late seventeenth-century engraving of Perth from Bridgend shows the outline of an assuming building standing gable-end on to the River Tay at the east end of the High Street, at the point where the medieval bridge across the river had stood until the early 1600s. The engraving is sadly lacking in much detail and the building is depicted partly shadowed, so we cannot be certain of its form by the late 1680s, when the Dutch military engineer John Slezer sketched his view of Perth from which the graving was worked up. We can be sure, however, that the building was the by-then modified chapel of St Mary at the Bridge of Perth. A chapel at the west end of the bridge, where it entered the burgh, had been recorded as early as 1209 when the original building, described as both ‘old’ and ‘on the bridge’, was swept away in the spate that destroyed the twelfth-century river-crossing. It was rebuilt on a grander scale and, if accounts of the architectural details that were seen during the demolition of the much-altered building in 1878 are to be accepted, was a richly-decorated thirteenth-century building on possibly two levels, perhaps an undercroft with the main chapel on the upper floor.

From the reign of Robert I (1306-29), when Perth began to emerge as the most regular seat of Scotland’s royal administration, where parliaments and councils met close to the coronation church at Scone, the still rudimentary nature of government institutions meant that there were no purpose-built ‘government buildings’. Instead, suitable spaces were pressed into service as and when necessary. In 1408, for example, St Mary’s served as a meeting-place for a council presided over by Robert, duke of Albany, at which resignations of property were made formally. The best known of these improvised spaces, however, was the church of the Blackfriars, which became one of the most favoured assembly-places for parliaments and general councils from the time of King David II (1329-71) onwards. Blackfriars was also the location of the King’s House, the residential complex used by the royal family when they were in Perth, which in James I’s reign included the Wardrobe. This was not simply the place where James kept his clothes, it was also his household cash office, the place from which his Treasurer – an office which James created – paid for the king’s personal and household daily expenditure.

Where, though, did the cash discharged by the Treasurer come from? This was the king’s income from his lands, rents, profits of justice, customs and tolls on goods, and general rights of lordship, received from all over the kingdom. From the twelfth century, Scotland’s kings had followed English examples in creating an administrative machine – the Exchequer – where their income could be accounted for, expenses identified and accounted for, and surpluses gathered. There was at first no building that was identified as ‘the Exchequer House’, for like all institutions of royal administration it was a mobile operation that followed the king and his officers around the realm. In the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, however, many of these institutions began to gravitate to Perth and it was St Mary’s Chapel that from 1406 to 1422 became the regular meeting place of the auditors of the Scottish Exchequer and then again regularly through James I’s reign. It was here that the sheriffs, bailies, custumars and other royal agents came to present their annual financial records, to hand over any cash surpluses, and account for debts and shortfalls in what they had gathered. In essence, the chapel was the nerve-centre of the royal financial machine and, for James I, would have been the place where he gathered the money that he needed to pay for his ransom and for his lavish building projects at Linlithgow and, of course, Perth.

Although it was the meeting-place of the Exchequer, it was not a building on which Scotland’s rulers were prepared to lavish much of their resources. Minor repairs were made to the chapel’s steps in 1401 but it was in 1406 that the auditors complained about the condition of the building in which they were carrying out such important work, for it was apparently no longer wind or watertight. Albany granted them 14s 10d, a significant but hardly princely sum of money, to carry out repairs. Further work to make the building weather-proof was authorised in 1414 and 1416.

It is one of the many ‘what ifs’ in Scottish history that St Mary’s might have evolved into a more permanent Exchequer audit chamber had James not been assassinated in the nearby Blackfriars in February 1437. Instead, the organs of government gravitated increasingly towards Edinburgh after that time and the chapel of St Mary reverted to its original purpose, a place of prayer for travellers preparing to cross the bridge and into the northern parts of the kingdom. After the Reformation, the building was spared and by the 1590s had been pressed into use as part of the burgh’s almshouse and survived the demolition of the main part of that building in the 1650s to provide materials for the fortification being built for Oliver Cromwell’s garrison on the South Inch. At the end of the seventeenth century, from which time the Slezer engraving dates, it had become part of the council building and its undercroft served as the Police Office until the final demolition of the whole complex in 1878 to re-open the east end of the High Street and make room for a new Town Hall and Council Chambers. Nothing now survives of what was once the financial heart of Scottish royal government.

The much altered chapel building, described in the seventeenth century as reaching three storeys in height, is probably represented by the tall gable in the centre of the image, just to the right and below the east gable of the parish church of St John.